Moving up and over to www.elizabethkaufer.com

Cutting Room Floor: Data Visualizations

I recently took a class on information visualization as part of my Msc at Oxford. For my final project, I created a series of visualizations based on data from Panos Ipeirotis’ 2010 demographic survey of workers on Amazon Mechanical Turk (link to paper + data). Unfortunately (fortunately?) for me, the final visualization had to fit on an A4 sheet of paper, so I had to excise a few graphs. Here’s what didn’t make the cut.

A classic bar chart, illustrating how long respondents had been on MTurk if it was their primary income source or not. I created all these graphs with Excel. With the exception of modifying the colors to match the color scheme on MTurk, this is pretty much an out of the box graph from Excel. Not a bad thing, but ultimately not part of the story I wanted to tell in my final visualization.

This is an example of a more minimalist bar chart. As Edward Tufte recommends in his book, The Visual Display of Quantitative Information, you should minimize the amount of non-data ink in your graphs, as it can be distracting and doesn’t necessarily make the chart easier to read.

The chart shows workers who work on MTurk because they find the tasks entertaining and how many HITs respondents completed per week. I cut this graph because my visualization was meant to be for a general audience who may not be familiar with MTurk. For the graph to make any sense, they would need to know what a HIT was and how long it typically takes to complete; this would have been too difficult to explain within the visualization.

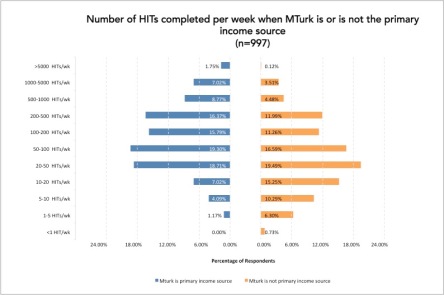

This is a tornado or butterfly chart showing the difference in number of HITs completed on MTurk per week depending on if MTurk is a worker’s primary income source or not. Unlike the other charts, which can be generated automatically and then further modified, Excel can’t handle a double x-axis so you have to trick it into making the chart by means of careful math and several different online tutorials. What I like about this chart is that you can pretty easily see the difference in the two distributions. This was slightly harder to see when the chart looked like the first example, with the bars next to each other. I wound up cutting this for the same reason as the second chart.

There were actually a few more than these three. Aside from the difficulties of the butterfly chart, making charts and graphs is pretty fun.

Instagram/Twitter uses of #Ferguson

Differences in user activity/behaviors in different social networks (also: Instagram research!) from bae Pew Research Center:

“In a new analysis of the #Ferguson hashtag on Twitter and Instagram, Pew Research Center has found some striking differences between the two social media platforms in how people use the hashtag and direct the conversation.”

Library Science + Internet

Two of my brilliant friends from the Oxford Internet Institute have created a super-interesting, cleverly-named podcast, Internet School Podcast, where they talk to people doing fascinating things on the Internet. And wow, people are doing such cool things on the Internet!

In a fun contrast to all the interesting and successful people they’ve interviewed, I was also on the show. I talked to them about library science and reading in their latest episode. Thank you Ellie + Eve for letting me yak about libraries!

P.S. Actual photo of me listening to the intro playback:

Continuing Research on Instagram

Who’s researching Instagram? What are they investigating and what are they missing? If that sounds at all interesting, take a look at a piece I wrote on academic research and Instagram for the student blog at the Oxford Internet Institute.

LibGuide on Digital Preservation

Last year, I created a LibGuide on Digital Preservation Resources for my class in Information Services and Sources. The guide is geared toward librarians, archivists, or basically anyone in a cultural institution who want to learn about digital preservation or needs to learn about it for his or her job.

Understanding digital preservation is crucial for anyone working with digital information, even if you don’t consider yourself a digital archivist. Maybe you are an academic librarian who needs to help professors come up with a data management plan for a grant application, or you work in an archive that has a lot of digital material and they need someone to be in charge of it. Many institutions wind up retraining employees to handle digital preservation tasks rather than hiring for that specific position. Handling digital preservation needs in-house, rather than outsourcing to private companies, is also vitally important for developing these kinds of skills and keeping it in the profession.

The best thing I learned from this assignment is that a ton of people are working on free, high-quality digital preservation resources. Although it’s a new area of library and information science, there’s a supportive community out there, setting standards, developing protocols, and crafting toolkits to jumpstart a digital preservation initiative at an institution.

#FollowBack: Issues Regarding Archiving Instagram

NB: This was a paper I wrote for my library school course, LIS 647 Visual Resources on May 5, 2014. I have not made any revisions or updates since that time.

Since the beginning of the twentieth century, our culture has become saturated with images, from advertisements to television to movies. With the proliferation of social media and cheap camera phones, that saturation has become all but complete. Images and photographs are hugely popular on social media. One of the most popular platforms, Instagram, revolves entirely around photographs created and shared by users. Instagram is a vibrant, information-rich record of contemporary history. It is used around the world by average people to celebrities to cultural institutions and captures anything from scenes of everyday life to world-changing events. It would not be outrageous to say that Instagram photos and other social media content will some day become part of the collections at archives and visual resource centers: the images created and shared on social media have been and will be vitally important to researchers, especially those interested in visual culture. But archiving an Instagram photo or other social media image is not like archiving other types of digital photography. Social media carries its own format and content idiosyncrasies, demanding a different kind of interaction by the archivist.

When the word “selfie” is chosen as the word of the year by Oxford Dictionaries, even the most conservative visual resource center must admit that the images of social media have a real, lasting place in visual culture[1]. Describing the discipline of visual culture, Beller writes, “What is visible, how it appears, and how it affects nearly every other aspect of social life is suddenly of paramount concern”[2]. This concept is exemplified in highly individualized, highly pervasive and image-heavy social media. For the visual resources community, this means their work has become more expanded, more difficult, and more important. An image shared on Instagram requires different archival considerations than a physical photograph or even a typical digital photograph, both technically and conceptually. As Gledhill observes (referring to digital content in general), “Building both the infrastructural capacity and methodological criteria for preserving this material represents a colossal paradigm shift for collecting institutions, whose identity has hitherto been constructed around materiality”[3]. Compared to analog formats, social media formats are somewhat unstable and often proprietary, making them highly liable for loss but also difficult to ingest into an archive. Social media platforms are constantly in flux, from the layout of websites, to the features offered or types of media supported, to the terms of service agreements users sign to continue using them. New social media platforms explode overnight and others disappear just as suddenly. This requires an enormous effort on the part of institutions to keep track of changes and adjust their archival practices if required. Some institutions may think that keeping up with trends across multiple social media platforms is too time-consuming and produces little to show for it, even if they maintain social media accounts themselves. However, it behooves collecting institutions to familiarize themselves with the way users engage with social media, not only for preserving any social media content the institution produces but also to prepare themselves to accept the future archival content from donors.

The content collected by archives and visual resource centers in the future will likely come from a variety of social media platforms, each with its own quality issues, metadata and file format standards[4]. It may not even come from the same user, but from many different users across the different groups of social media sites. Many archives are facing these problems now, such as the institutions trying to collect the social media ephemera of the Occupy movements. Part of the challenge is convincing content creators–many of whom may not even be aware of the concept of metadata–how to save important metadata and optimize their content for archival submission. The Activist Archivists, a group of New York archivists who charged themselves with archiving the Occupy Wall Street protest, encouraged protesters to distribute content under the Creative Common license so it could be archived without the standard, exclusive donor agreements. They also created short informational videos and postcards with tips on why archiving the movement was important and how protesters could make sure their content was in the best shape to be archived[5]. These informational items were short, easy to understand, and encouraged creators to collect as much information about the context of their content. They also advised not to upload to sites that would remove metadata: many commonly used services, such as YouTube or Vimeo, strip metadata when content is uploaded onto their sites[6]. Archives and visual resource centers may want to consider creating platform-specific creation/archival guides like the Activist Archivists’ for users who want to donate their social media content or for staff members who manage social media accounts for their institutions. Familiarizing themselves with the quirks of popular social media platforms will only better prepare them to archive this type of content in the near future.

Archiving social media is not without controversy. Users tend to feel strongly about their privacy, and feel that social media accounts–even if they are publicly available on the Internet–are personally “owned” by them and therefore private. This is particularly true for photos, which are often highly personal. In a survey about institutional practices for archiving social media, respondents tended to perceive photos as more personal than other types of social media and expressed concern about the potential loss of privacy and contextualization if those photos were archived by an institution[7]. Large scale archiving of social media sites may not be well received by users, who may feel that their privacy is being eroded. The safest course of action for institutions would be to focus on archiving their own social media accounts and/or social media content that has been donated. But even limiting an archive just to one’s own social media accounts will still involve the capture of personal information from outside users, for example, a user who comments on an Instagram photo. Therefore, institutions need to define their archiving boundaries clearly to put content creators and users at ease: the purpose of the archive, the type of access available, creator attribution, and use of archive material must be explicitly stated by the institution[8]. For example, the Smithsonian has made the decision not to archive the profiles of users who like or follow their social media accounts. However, they do capture comments and any account information linked to those[9]. Ultimately, the institution must be sensitive to the types of personal information present on different social media sites and individually determine whether or not it could breach a user’s privacy to archive it.

Despite the difficulties, there is much an institution can gain by archiving social media. Social media items, like any the content on the web, has no guarantee of permanence: just because something is online, does not mean it will last forever or be preserved. Based on research conducted by SalahEldeen and Nelson on embedded resources in tweets, 11% of web resources shared via social media disappear after a year, and then continue to disappear at a rate of .02% per day[10]. Within an institution, there may be unique content that is only found on social media accounts. This content has a high risk of being lost if the social media service goes out of business or suffers a catastrophic data failure. Cultural institutions should make sure that their content is preserved by taking action themselves, rather than hoping the social media company will handle it. Furthermore, social media may fall under certain recordkeeping requirements. Government agencies have a legal requirement to archive their social media; the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) observed that “Content on social media is likely a federal record”[11]. Preserving social media also represents an opportunity to archive the images of marginalized or controversial groups, for example the Occupy movement[12]. The Occupy movement used social media heavily, using photos and video to document their protests and abuses at the hands of law enforcement. The images from Occupy are an important document of the early 21st century. Including them in an archive or visual resource collection would not be unusual, but figuring out the best way to add these images to an archival collection requires a little creative thinking. Archiving social media is exciting challenge, demanding careful thought and unique problem-solving from the part of the archive or visual resource center.

Since social media archiving is a relatively new practice, there is no one standard way to carry it out. Archival methods for social media are mostly homegrown and take a variety of forms. Identifying significant items among what can only be described as a deluge of material poses a huge challenge for archivists. When determining whether or not an item on social media should be archived, certain questions should guide the assessment process, such as, Is this content unique to the social media platform or is it available elsewhere? Does it convey important information? Could it constitute an official business record?[13]. Rate of capture is also an important consideration in the fast-moving world of social media, but figuring out how to capture it can be an even bigger challenge. Many social media services do not allow a user to export his or her data. While Twitter and Facebook both allow users to download an archive of their entire history and content, Instagram does not even allow users to download individual images except by right-clicking “Save As.” This makes it highly labor intensive to save images, since any metadata must be added manually. Some institutions take screenshots of different social media pages, others simply copy and paste content into word processing documents[14]. The Smithsonian Institution maintained nearly 80 Facebook pages in 2011, so the Smithsonian Institution Archives made the decision to archive a “representative sampling…to document how the Smithsonian used new technology in the early 21st century” besides archiving unique content[15]. In their case, they opted to capture the Facebook pages in PDF/A format. The PDFs must be completely self-contained, without audio or video. However, this process is time-consuming as the capture and cataloging cannot be automated: each page was manually opened and printed to PDF/A. By 2012, the Smithsonian had over five hundred social media accounts across various platforms, including Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Flickr and blogs. Each of these focused on a different audience and contained different, specialized content[16]. Rather than archiving each of these accounts in their entirety, which would be too time-consuming and ultimately duplicative, the Smithsonian developed a special appraisal process for their social media accounts. Each account is reviewed individually to determine how much original, important content it contains. If the amount of unique content is great enough, the entire account is captured. Otherwise, only a sample of the account is captured to demonstrate how it was used[17]. Sometimes the content is crawled, other times it is exported into a spreadsheet or XML document. The Smithsonian’s approach represents a relatively straightforward, manual procedure for archiving that evolves as their social media needs grow and change. This homegrown approach may be the most useful and flexible for most institutions, since at present there are limited archival tools designed to archive social media. There are some third-party archival services available specifically for social media, and some of these are platform-specific. Most of the archival tools for social media are geared towards a lay audience, i.e. users trying to archive their personal collections, rather than an archive or library working off a preservation standard. After selection criteria and capturing methods have been determined, two core archival tasks need to be considered: how the items are captured from the web and how they are catalogued so they are made accessible.

Figure 1. A typical Instagram post contains many layers of information.

Image-heavy social media content may be adequately cataloged by existing content standards and metadata schemas such as VRA Core and CCO. However, it may be some time before the standards’ committees formally develop and publish how social media images should be cataloged. Until then, visual resource centers and archives will need to adapt their current cataloging practices to fit social media as best they can. The nature of social media makes it difficult to fit neatly into existing cataloging standards. For instance, could a user’s entire social media account be considered a “collection” under VRA Core, or should a collection be more narrowly defined, such as every post with a specific tag (e.g. #CapeCod, #wedding)? The cataloger must also understand the “culture” of a social media account to best capture important information. Consider hashtags: on Instagram, users add hashtags as both a folksonomy classification and also a way to comment on their post (like an aside in a theatrical production). Understanding how a user utilizes hashtags in a particular post will affect how it is cataloged. A cataloger may look at one hashtag (e.g. #gradschool) to guide how she completes the Subject field, while recognizing that another hashtag (e.g. #wishIcouldlivehere) is really a part of the caption and not a classification tag from the user. Further adding to the challenge is the sheer amount of information that social media posts and images consist of. A single Instagram photo contains multiple layers of information: there is the photo and its subject, the caption, the tags, the geographic location, the “likes” from other Instagram users, and comments. Deciding how VRA/CCO will be used to catalog all these pieces of information requires mindful consideration and a clear understanding of how the culture of Instagram operates. For example, take the Location field for CCO. A user may add her geographic location to an Instagram photo, but it may not be something found in the Getty Thesaurus of Geographic Names: sometimes a user marks her location as “Home” while still capturing GIS data. How should these two separate locations–the meaningful one marked by the user and the actual physical location–be cataloged? Even a field like “Title” poses a conundrum. Is the caption of an Instagram photo a title? If not, under what field should the caption be recorded? There are several ways an Instagram photo or other social media post can fit into VRA/CCO depending upon the needs of the archive and the nature of the social media collection. Although each social media platform has its own particular quirks and user practices, a cataloging practice developed for one platform may easily apply to another. An Instagram post is not all that dissimilar from a Twitter post with a photo in terms of information content. Adapting VRA/CCO for social media will allow archives and visual resource centers to accept social media collections and make them accessible to users, placing them at the cutting edge of web archiving and establishing a good procedure for future digital submissions. In time, there may even be archival tools developed specifically for archiving Instagram and other social media sites. Currently, the field is rather slim.

Instagram itself does not offer any native archiving feature. Users are not able to download images at all, let alone with any sort of contextual information or metadata. This makes it a challenging service for librarians to archive. For digital image files, technical metadata is not sufficient; descriptive metadata should also be directly embedded into an image file to create a completely contained object[18]. And there is a lot of metadata that can be added. On Instagram, users may add geographic locations, captions, tag other users, but it is not clear what is automatically recorded by Instagram if users do not manually add any descriptive information. Limited metadata is displayed in the Instagram post, and can be edited by the user. An Instagram post displays the user who uploaded the image (although this may not be the user who took the photo), an optional caption (which may include manually added hashtags), an optional geographic location, and optional tagging of other Instagram users. The date is not displayed, but rather a relative time of when the post was uploaded (e.g. “5d” for “5 days ago”). But none of these information is transferred when images are downloaded from Instagram. According to tests run by the Embedded Metadata Manifesto initiative, Instagram strips embedded metadata if image files are saved from a web browser and does not allow images to be downloaded directly through its user interface[19]. Ideally, a social media archiving service would be able to pull all of these information from an Instagram post, but not every service is able to properly capture metadata or even the image itself. Certain social media curation services, such as Storify, merely create the appearance of preservation without actually archiving resources: if a resource is removed from the original source, it also disappears from the curated collection[20]. The options for archiving one’s Instagram account are relatively limited. Two third-party options are Recygram and Instaport. While these programs were not created with an archival audience in mind, they were tested to see if they could be of any use to an archive or visual resource center, or even if they could be recommended to potential donors to compile their Instagram posts for archival submission. The review was guided by the following questions: How much can be downloaded at once? Can the user select specific items to download? What format is it downloaded in? What is the quality? What information is captured? How easily can this be turned into an submission ready for archiving? The answers to these questions were not promising. Both of these are geared toward a casual Instragram user and unfortunately would have very limited applications in an archival setting.

Recygram (http://www.recygram.com/) is an app available on iPhone only. It requires you to log in to your Instagram account from the app, which gives Recygram authorization to access basic account information, and also allows it to comment or like photos you post. The application can send Instagram photos directly to Flickr or Tumblr, save to the iPhone’s camera roll, or save to a zip file. The user can select all photos or designate specific photos save. The zip file may be sent to email, Google Drive, Dropbox or other sharing apps such as Evernote. The zip file downloads Instagram photos as 640 × 640 jpegs. An image file contain no embedded metadata, and the file name is a completely random string of letters and numbers. To upload an Instagram photo to Flickr requires giving Recygram access to the Flickr account, to upload/edit/replace photos, and to interact with other members’ photos (e.g. comment, favorite). This seems like giving Recygram a little too much control over the Flickr account, but it is unclear what giving Recygram the ability to comment on other users’ photos truly entails. Several times, the application unexpectedly quit when trying to load additional Instagram photos to select. Again, when uploading to Flickr, Recygram included no metadata and gave the photo a random string of numbers/letters as a file name. While the application is very easy to use, the fact that it exports no metadata and can only be used on iPhones (not even iPads) makes it practically useless for an archival institution. A few reviews of the product make the case that Recygram is very learnable and makes it simple to quickly move your entire Instagram archive to other social media services such as Flickr or Tumblr[21]. While this could be a useful feature, because Recygram captures no metadata and does not use descriptive file names, it would require a lot of additional work by the archivist to create even a minimum amount of metadata to add the images to Flickr or Tumblr, let alone preparing it for addition to an archive. Another third-party service for archiving Instagram is Instaport, which had some greater flexibility but ultimately had the same problems as Recygram.

Instaport (http://http://instaport.me/) is a web-based service, so unlike Recygram it can be accessed from any computer. By signing in with Instagram, you authorize the service to access basic account information. Instaport allows you to export all photos or select photos based on specific criteria, such as within a certain timeframe (e.g. the last 10 photos taken), photos taken between specific dates, photos which you liked, or photos tagged with a specific hashtag. The hashtag option cannot be limited by time and there is a max of 500 photos that can be downloaded with this option, so if the same hashtag is used constantly this could produce duplicated captures or miss the 501+ photo. It takes a few minutes for the site to produce a zip file which can be directly downloaded to your computer. The download date is included as part of the zip file’s filename. As with Recygram, the photos are downloaded as 640 × 640 jpegs. However, unlike Recygram, the filename for each photo includes a unique identifier and the date the photo was uploaded to Instagram. This is a more useful file naming system than Recygram’s and provides an easier way to track photos. However, no other identification information or metadata is downloaded. While Instaport is more useful than Recygram and allows for more specific types of file selection, it is still very limited for an archival institution’s needs. In both cases, the quality of photos is generally poor, but this seems to be a problem originating in Instagram. Panzarino observes that the service is a good way for a photographer to quickly create a backup of his or her Instagram photos[22]. However, like many social media archiving services, Instaport is better suited to individual users just trying to manage their own personal photos or move a large amount of photos from one service to another. An individual user may be frustrated that Instaport does not capture any photo details, but overall he or she is less likely to be concerned with its lack of metadata than an archivist. Until more robust archiving tools are available, many institutions will have to be creative and flexible in order to archive social media.

Social media presents a unique challenge for archives and visual resource centers. While some archival tools have been developed, we are still a long way from having a single, efficient tool that could capture and prepare social media content for an archive. Until then, institutions will need to develop individual solutions that best fit their own needs, whether it is just archiving their own social media presence or capturing content from users across the web. Similarly, developing cataloging procedures that adequately serve social media items will require careful thought by catalogers and metadata specialists. Archiving social media requires many new archival practices and procedures, demanding a substantial effort on the part of archives and visual resource centers. Social media is a key record of our present history and will become an integral part of archives in the future. While the task of archiving social media appears burdensome, the investment of time and effort to develop best practices will be vital to the archives and users of the future.

Footnotes

[1] Brumfield, B. (2013, November 20). Selfie name word of the year for 2013. CNN. Retrieved from http://www.cnn.com/2013/11/19/living/selfie-word-of-the-year/

[2] Beller, J. (2005). Visual culture. In M. C. Horowitz (Ed.), New Dictionary of the History of Ideas (Vol. 6, pp. 2423-2429). Detroit: Charles Scribner’s Sons. Retrieved from http://go.galegroup.com/ps/i.do?id=GALE%7CCX3424300803&v=2.1&u=nypl&it=r&p=GVRL&sw=w

[3] Gledhill, J. (2012). Collecting Occupy London: Public Collecting institutions and social protest movements in the 21st century. Social Movement Studies, 11(3/4), 342-348.

[4] Besser, H. (2013). Archiving aggregates of individually created digital content: Lessons from archiving the Occupy Movement. Preservation, Digital Technology & Culture, 42(1), 31-37. doi: 10.1515/pdtc-2013-0005

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Marshall, C.C., & Shipman, F.M. (2012). On the institutional archiving of social media. In Proceedings of the 12th ACM/IEEE-CS Joint conference on Digital Libraries (pp. 1-10). New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Wright, J. (2012, June 13). To preserve or not to preserve: Social media [Web log post]. Smithsonian Institution Archives. Retrieved from http://siarchives.si.edu/blog/preserve-or-not-preserve-social-media

[10] SalahEldeen, H. M. & Nelson, M. L. (2012). Losing my revolution: how many resources shared on social media have been lost? In P. Zaphiris, G. Buchanan, E. Rasmussen, & F. Loizides (Eds.), Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Theory and Practice of Digital Libraries, TPDL 2012 (p. 125–137). New York, NY: Springer.

[11] Quoted in Moore, J. (2013, November 25). Social media: The next generation of archiving. FCW. Retrieved from http://fcw.com/articles/2013/11/25/exectech-social-media-archiving.aspx

[12] Gledhill, 2012.

[13] Moore, 2013.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Fuhrig , L.S. (2011, May 31). The Smithsonian: Using and archiving Facebook [Web log post]. Smithsonian Institution Archives. Retrieved from http://siarchives.si.edu/blog/smithsonian-using-and-archiving-facebook

[16] Wright, 2012.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Reser, G., & Bauman, J. (2012). The past, present, and future of embedded metadata for the long-term maintenance of and access to digital image files. International Journal of Digital Library Systems, 3(1), 53–64. doi:10.4018/jdls.2012010104

[19] Embedded Metadata Manifesto. (2013). Social media sites: Photo metadata test results. Embedded Metadata Manifesto. Retrieved from http://www.embeddedmetadata.org/social-media-test-results.php

[20] SalahEldeen & Nelson, 2012.

[21] LeFebvre, R. (2013, March 1). Archive, batch send, and download your Instagram photos with Recygram [Web log post]. Cult of Mac. Retrieved from http://www.cultofmac.com/218098/archive-batch-send-and-download-your-instagram-photos-with-recygram-ios-tips/

[22] Panzarino, M. (2011, July 1). Instaport: Download your entire Instagram archive for backup or upload. The Next Web. Retrieved from http://thenextweb.com/apps/2011/07/01/instaport-download-your-entire-instagram-archive-for-backup-or-upload/

Usability Testing of Google Glass

NB: This was a paper I wrote for my library school course, LIS 644 Usability on May 10, 2014. I have not made any revisions or updates since that time.

Usually, usability testing of a new product happens behind the scenes. One popular method, user testing, takes place in a controlled environment, where participants are gently guided by usability experts and data is meticulously collected and analyzed. Participants are carefully recruited, often to capture a representative sample of a population, and perhaps rewarded with a token of appreciation for their time and effort. User testing is a solid, reliable research method that is well-established in the usability field, even considered to be the best method of evaluation[1]. Yet when it came time for Google to test the market version of their wearable computer, Google Glass, it seems like the usability experts said, “Actually, let’s do the opposite of all that.” They decided to make participants compete to join the test, made them pay over a thousand dollars to purchase the very device they were testing, and publicized the entire research project, called the Google Explorer program.

On the surface, the Google Explorer program seems closer to a guerilla testing method than more traditional usability research, in that the goal of the program was to evaluate real world usage and direct feedback from users without the rigidity of a lab test. But even guerilla testing methods tend to involve a certain degree of control, such as observation by the researcher or using predetermined tasks users need to perform during a test. As an emerging research method, there does not appear to be one single way experts carry out guerilla usability testing. However, most still retain the trappings of traditional user testing: moderator, a single environment, a limited time for testing, note-taking/data gathering by moderator. A key advantage of guerrilla usability testing is that it is cheap and quick; Unger and Warfel observe that guerilla testing is ideal “when you are battling against time and money limitations”[2]. The testing for Google Glass turned all this on its head. Google didn’t need to save money: it’s Google. Recruitment doesn’t seem to have been a problem either. They actually got their participants to fight to be selected and then pay Google for the privilege of joining in on the testing. Users were tasked with crafting a 50-word application tagged “#ifihadglass” and post it to Google+ or Twitter. Winners would need to purchase a device for $1,500 and attend a training session (or “special pick-up experience,” in Google’s words) in New York, Los Angeles or San Francisco, which means some participants would need to travel out-of-state to be involved in the testing[3]. Few companies but Google could make such demands on recruits and still have to turn candidates away. The Google Explorer program was clearly not the only research method Google employed during their design of Google Glass: the question is why they decided to do it at all. Time and budget constraints probably aren’t a problem for a company like Google, so what is the advantage of using something like guerrilla usability testing?

The primary purpose of the Google Explorer program was to determine what users will actually do with Glass in real life. It sent participants out into the world seemingly without direction. Google seems to have collected feedback by soliciting stories and content from “the Glass Explorer Community,” which is an online community where Explorers interacted with each other and with Google directly[4]. We do not know how else Google solicited feedback, if they asked for it a specific way (such as questionnaires, diary studies, etc.), or how they analyzed the feedback they received. And since the Explorers actually own their Google Glass devices, it isn’t clear when the testing period is actually over. Does it last as long as the device holds up? Are Explorers under any kind of obligation to report back to Google for a certain period of time? Explorers heavily utilized public social media accounts to record their experiences with Glass, and Google collected a lot of that content from users to put on its website (http://www.google.com/glass/start/explorer-stories/). Using social media to carry out usability evaluations has exciting potential. By asking users to document their feelings and experiences using social media, users can contribute in a more natural way than using a diary form or survey. It has the potential to capture more holistic feedback, encompassing both emotional and pragmatic reactions (MacDonald & Atwood, 2013). However, one would imagine this places a significant burden on the researchers to clean up what is likely a huge amount of inconsistent data for analysis. Unlike many usability tests, Google did not receive feedback just from their participants: the Explorer program also inspired a huge response from outside the community.

The Explorer program was unlike a typical usability test. It was on a large, public scale, and the very visible testing of Google Glass produced a lot of commentary from both the tech community and outside observers, including Congress. They expressed concerns about privacy and etiquette, even even coining a new term “glasshole” for obnoxious Glass users (one wonders how the widespread use of the word “glasshole” would be discussed in a usability report). Some Google Glass users have experienced violence as a direct result of the product. Mat Honan wore Google Glass for a year, and remarks, “People get angry at Glass. They get angry at you for wearing Glass. They talk about you openly. It inspires the most aggressive of passive aggression” (2013). Honan also observed that since the application requirements to test the product were widely known and had a high cost barrier ($1,500), non-users sometimes felt Google Glass and/or its users were privileged or snobbish[5]. However, strong emotional reactions are still valuable to researchers, even when the reactions come from people who coexist with the product rather than use it: Google has been paying attention to the chatter around appropriate codes of conduct. One significant result of the Explorer program related to how users should interact with the world around them when using the product. In February, they posted an etiquette guide for Glass users (https://sites.google.com/site/glasscomms/glass-explorers), specifically asking users not to be “glassholes” and advising users how to better engage with both the product and the world around them. (Presumably, Google also decided to make other changes to the Glass interface based on the feedback collected from Explorers, but this was not publicized.) For such a groundbreaking product, the Explorer program was an invaluable way for Google to figure out not only if there were any usability problems with the product itself, but all aspects of a user’s experience–including reactions of people around him or her.

Is the Google Glass Explorer program a sound usability testing method, or just a PR stunt? Perhaps it is a little bit of both. Some of the content from the Explorers, including photos and videos, has been compiled on the Google Glass site for anyone to view. It’s a great advertisement for Glass, but also gives important insights into how people might use wearable technology. Putting a new interface or product out in the wild with real users gives a usability expert less control over the test, but provides real, valuable data on how users will actually interact with the product. Additionally, public testing might help companies understand how non-users perceive their products and what affect that might have on user experience. While usability tests of other products may not command the same amount of publicity as a Google product, the Explorer program is a valuable look at how the combination of social media and in the wild testing can provide natural feedback on a product.

Footnotes:

[1] MacDonald, C. M., & Atwood, M. E. (2013). Changing perspectives on 4valuation in HCI: Past, present, and future. In CHI ’13 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI EA ’13). ACM, New York, NY, 1969-1978.

[2] Unger, R. & Warfel, T. Z. (2011, February 15). Getting guerilla with it. UX Magazine. Retrieved from https://uxmag.com/articles/getting-guerrilla-with-it

[3] Ulanoff, L. (2013, February 20). Want Google Glass? Tell Google how you’ll use it. Mashable. Retrieved from http://mashable.com/2013/02/20/get-google-glass/

[4] Google. (n.d.). Explorers. Google Glass. Retrieved from https://sites.google.com/site/glasscomms/glass-explorers

[5] Honan, M. (2013, December 30). I, glasshole: My year with Google Glass. Wired. Retrieved from http://www.wired.com/2013/12/glasshole/

Strategic Proposal: Maintaining Wikipedia Entries for Emerging and Living Artists

NB: This proposal was originally written for my library school course, LIS 655-01 Digital Preservation, at Pratt Institute. The assignment was to propose a way for a cultural institution to use Wikipedia in its strategic planning and/or to help carry out its mission. I am not affiliated with either WCMA or MASS MoCA and this was written without their input.

Proposal

Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (MASS MoCA) and Williams College Museum of Art (WCMA) should consider incorporating Wikipedia into their online presence by creating and editing pages for contemporary artists and artworks in their collections. Doing so would not only contribute to the field of scholarship of contemporary art, it would also draw a larger audience to the digital collections of WCMA and MASS MoCA. Wikipedia is a free, easy-to-use platform which could easily be incorporated into existing marketing and publication models, and represents a potential audience of thousands of new users (including students, researchers and casual browsers) for WCMA and MASS MoCA’s digital educational resources and image collections.

Background

The Berkshires in western Massachusetts are known as a cultural haven for visual and performing arts. Two of its most popular art institutions are MASS MoCA and WCMA.

MASS MoCA is a contemporary visual and performing arts museum located in North Adams, Massachusetts. Its stated mission is to “catalyze and support the creation of new art, expose our visitors to bold visual and performing art in all stages of production, and re-invigorate the life of a region in socioeconomic need”.[1] It embodies this mission by exhibiting new art and artists, granting artist residencies, and providing numerous educational programs. The museum is a converted industrial site with warehouse spaces ideal for large installations and unconventional artworks. The museum has been a boon to the regional economy as well: according to MASS MoCA, it generates $20 million per year.[2]

Just a short drive away is WCMA, the art museum of Williams College in Williamstown, Massachusetts. It is an integral part of the college campus and the community, regularly hosting classes from the college and tours for elementary school children. It has a strong teaching mission, and focuses on collecting works that support the curriculum of Williams College classes and have strong educational potential.[3] Like MASS MoCA, it cultivates contemporary art, serving “as a laboratory for the production, exhibition, and critical discussion of works by living artists”.[4] Each of these museums houses unique collections that include fostering the work of contemporary and local artists. They work closely with educational and scholarly communities (from elementary to college and university levels), with stated missions that focus on teaching. WCMA has an online digital collection already in place, which includes high quality images and teaching materials for K-12 educators.

Assets and Strengths

Both museums have strong ties to the local community and provide invaluable support to emerging artists. They have well-established reputations in the art world. They utilize art history and fine arts students at nearby colleges in their internship and educational programs. Both museums also have strong institutional support. WCMA is a department of Williams College, and engages closely with the college on using art to teach across departments. MASS MoCA has already completed two phases of renovation on its site, and is set to expand its gallery and performing arts spaces even further through $25 million in funding from the state government.[5] With these strong assets, both institutions are vital proponents of education and new art.

Opportunities for Improvement

However, there are some significant challenges these museums must deal with on an ongoing basis. While the Berkshires are a popular tourist destination, its location is relatively remote, making it more difficult to engage with users from outside the Berkshire region. WCMA addresses this issue with its online digital collections. It currently has a 13 separate digital collections available on its website, but the interface is somewhat limited and unappealing. MASS MoCA archives its exhibition information online, but does not have a searchable digital collection of artworks. Their educational outreach focuses on users who can actually visit the museums in person. WCMA has tried to remedy this by providing K-12 art history teaching guides on its website and creating two online education modules for Egyptian and Indian Art. Yet these resources are limited in scope, with only a handful of images available within the education modules. None of the contemporary art exhibited at WCMA is included in the education modules, just in the downloadable PDF teaching guides.

Plan of Action for Wikipedia

These museums would greatly benefit both their institutional reputations and further their educational missions by increasing their online presence. They could create and bolster their digital collections, revamping and redesigning their websites, and aggressively marketing themselves on social media, all at a high cost of time, money and effort. But there is another, easier way they could augment their digital output which would directly benefit the institutions, their artists, and their educational users. They could become editors for the popular online encyclopedia, Wikipedia.

WCMA and MASS MoCA should develop a Wikipedia editing project that incorporates the below items (in increasing order of time/effort):

- Editing and expanding existing Wikipedia pages on WCMA, Williams College and MASS MoCA

- Editing and expanding existing Wikipedia pages on emerging artists

- Creating new Wikipedia pages for emerging artists

For the first option, WCMA and MASS MoCA simply take more involvement with the management of their own separate Wikipedia entries. For example, WCMA could add a list of public artworks on campus to the page for Williams College or create a list of recent exhibitions on its own Wikipedia page. The second and third options involve more active engagement. Both institutions would edit or create Wikipedia pages for the living artists they have or will exhibit. Creating entirely new pages would involve the most amount of work, but present the most benefit to the artists involved. At the very least, WCMA and MASS MoCA should take charge of their Wikipedia presence and become more involved in editing and enhancing their Wikipedia entries.

Utilization of Existing Assets

Both WCMA and MASS MoCA exhibit new, emerging and contemporary artists and often collaborate on these kinds of exhibitions, sharing share curatorial and editorial resources. For example, in 2008, the two museums (along with the Yale University Art Gallery) launched a retrospective of Sol LeWitt’s wall drawings at MASS MoCA.[6] This makes them ideal partners for working on adding new artists to Wikipedia.

The Wikipedia project may be accomplished by utilizing existing staff in the publication marketing department or intern and volunteer college students. Both WCMA and MASS MoCA already have internship and volunteer programs in place, so it would be straightforward to add Wikipedia duties to existing positions. Many of these interns and volunteers study art history at Williams College or other nearby schools, so this would provide a vital educational opportunity for students to conduct research and add to the scope of knowledge in a real, tangible way. With online tools, scholarship is changing, and Wikipedia is just one of the ways academia now engages online. Supporting Wikipedia in this way would demonstrate that WCMA and MASS MoCA are also on the cutting edge of education, not just art. WCMA may also collaborate with the faculty of the Williams College Art History Department on a class assignment to create/edit pages for living artists. The relationship between the department and the museum is already close, and faculty could be open to the idea of giving students the chance to actually publish their art history research in a well-known forum.

Opportunities for Exposure and Scholarship

By using Wikipedia, each institution has the chance to link their digital images and scholarly information with a popular research/discovery platform. The point of digital collections at WCMA was to try and reach a wider audience than those that would be able to come into the museum itself; incorporating images and information into a hugely popular platform like Wikipedia would better serve that mission. Rather than trying to build an audience and a marketing campaign from the ground up, WCMA and MASS MoCA would harness the community of users on Wikipedia. Images could be added to Wikimedia as well Wikipedia, taking advantage of another platform that is already popular with students and educators. An ongoing Wikipedia project would be especially important for increasing the exposure of emerging artists who may be underserved or not represented in Wikipedia at all. Wikipedia could serve as an in-progress digital artist file and catalog raisonne, where information such as lists of important works, exhibition histories, artist statements, and artistic styles could be collected into one place instead of scattered throughout the Internet on different museum, gallery or artist websites. For example, MASS MoCA’s Wikipedia page contains a list of past exhibitions. Yet many of the artists who participated in those exhibitions do not have Wikipedia pages at all. MASS MoCA already has exhibition images and information; it would not be difficult to create an artist page from that content. One advantage of Wikipedia is that creating a page also creates opportunities for other users to add new information.

Editing Wikipedia would also increase exposure for WCMA and MASS MoCA themselves. While MASS MoCA has a rather extensive Wikipedia page already, WCMA’s entry is only a few, uncited lines. Neither WCMA’s nor Williams College’s Wikipedia pages mention anything about the artwork in WCMA’s collection or public artworks on campus. Jenny Holzer and Louise Bourgeois have two sculptures on campus. Holzer’s piece is listed on her Wikipedia page, but Bourgeois’ is not. These artworks received extensive press when they were installed and are beloved by both students and visitors, but as far as Wikipedia’s users are concerned, these pieces are marginal. Both institutions already create and publish content regarding their artists, artworks, and exhibitions. If one searches for “Jenny Holzer” and “Williams College,” the first three results are from the WCMA website: the content often exists and has already been vetted by the institution. A Wikipedia project would merely add another venue for publication. WCMA and MASS MoCA have an amazing opportunity to add directly to a hugely popular research site, increasing exposure for their own institutions and for the artists they champion.

Potential Drawbacks and Solutions

At first glance, there may be some downsides to an ongoing Wikipedia project. First, any Wikipedian candidate must be trained to use Wikipedia and training materials should be produced. Then, there is the cost of time and effort on the part of Wikipedians and review by supervisors. Wikipedia articles and edits demand the same rigorous, high-quality production and review that any institutional publication merits. If interns or other non-subject specialists are responsible for editing or creating Wikipedia articles, there must be some sort of editorial oversight. Even if the content is created by curatorial and/or marketing staff and merely uploaded into Wikipedia by interns, some sort of review process would need to occur. As with any digital project, copyright must also be taken into consideration if images will be uploaded into Wikimedia.

However, none of these issues are insurmountable with careful planning, and the benefits far outweigh the downsides. Wikipedia already maintains training and help documentation, which supervisors at WCMA and MASS MoCA could base their training documentation off of. It is not a particularly difficult system to learn, especially since it is probably already very familiar to potential editors. For reviewing articles, this may be accomplished as part of a regular editorial, curatorial or marketing review process; copyright issues would also be resolved during this time. If editing Wikipedia is part of a class assignment, professors can review as part of the grading process. Working together to share artist information and creating documentation would lessen the burden on each individual institution. It also opens up additional educational and special event opportunities for students and interns, like site visits, archival tours, or group edit-a-thons at either museum location.

Conclusion

Wikipedia is a powerful tool with a huge built-in audience and support community. Utilizing it accomplishes multiple important tasks for the museums and for contemporary art as a scholarly discipline. By creating and editing articles on Wikipedia, WCMA and MASS MoCA can directly enhance their own reputations, further their educational missions, and support emerging artists.

References

[1] Our mission. (n.d.). In MASS MoCA: Museum of Contemporary Art. Retrieved from http://www.massmoca.org/mission.php

[2] As cited in Cook, G. (2014, March 6). MASS MoCA plans to double its size with $25.4 million from state. WBUR: The ARTery. Retrieved from http://artery.wbur.org/2014/03/06/mass-moca-double

[3] Building a teaching collection. (n.d). In Williams College Museum of Art. Retrieved from http://wcma.williams.edu/collection/building-a-teaching-collection/

[4] Mission. (n.d.). In Williams College Museum of Art. Retrieved from http://wcma.williams.edu/about/mission/

[5] Cook, 2014.

[6] Ibid.

First Conference I Never Attended: QQML’14

Exciting news: I’m thhhhhis close to achieving my first academic publication. Last semester, my Human Information Behavior class (which consisted of two other students and our professor, Dr. Pattuelli) conducted a three-part study on e-book usage among college students. Our abstract on the study was accepted at the 2014 QQML conference in Istanbul, which means it will also be published in the conference proceedings. Unfortunately, I will not be able to attend the conference but Dr. Pattuelli will be able to go and present our research. (Tho I’m less annoyed about missing the conference than missing a chance to see Hagia Sophia because duh it’s amazing).

The International Conference on Qualitative and Quantitative Methods in Libraries (QQML) is an interdisciplinary conference which focuses on the development and use of quantitative and qualitative research methods in libraries, which is very cool and super relevant to my general user experience/research interests. This year, Pratt Institute is coordinating a session on academic e-book adoption/practices in libraries under the direction of Dr. Irene Lopatovska and Dr. Cristina Pattuelli.